The Mozambican painter and poet Malangatana Ngwenya, who has

died aged 74 following respiratory complications, was one of Africa's leading contemporary artists, and his work is known round the world.

A lifelong Marxist, he depicted the suffering and struggles of a

troubled nation, and campaigned for peace. While Ngwenya,

meaning crocodile, provided the title of a 2007 documentary film,

he was most widely known as Malangatana.

Once Mozambique had achieved independence and freed itself from conflict, he encouraged its continuing cultural life. A National Art Museum was established in the capital city of Maputo, and the art college Núcleo de Arte became primarily concerned with encouraging

young, black artists.

Núcleo de Arte was where Malangatana had started evening classes

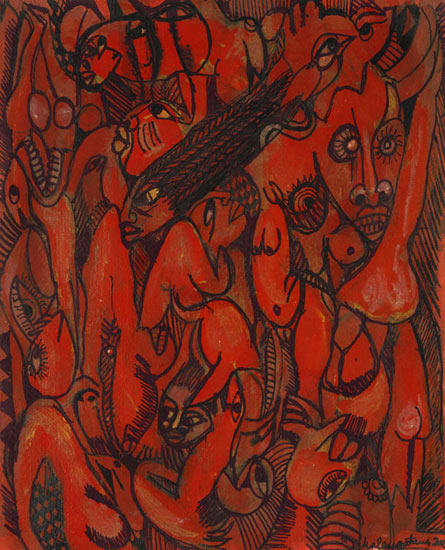

in 1958, followed three years later by his first solo exhibition. He courageously presented his ambitious Juízo Final (Final Judgment),

a commentary on life under oppressive Portuguese rule. Mystical

figures of many colours, including a black priest dressed in white,

evoke a vision of hell. Some of the figures have sharp white fangs,

a recurring motif in Malangatana's work, symbolising the ugliness of human savagery.

Fame soon followed, as his works were toured and seen abroad.

A year after his first show, the German champion of African arts Ulli Beier pointed to Malangatana's originality. In 1963, he contributed to

the anthology Modern African Poetry published by the journal Black Orpheus, and soon after became an active member of Frelimo, the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique. The following year, he was detained by the PIDE, the Portuguese secret police, and sentenced

to 18 months' imprisonment. Among the congenial company he

found behind bars was the country's leading poet, José Craveirinha.

Malangatana at his home in Maputo, Mozambique, in 2005. Photograph: Martin Godwin

Malangatana at his home in Maputo, Mozambique, in 2005. Photograph: Martin Godwin

Malangatana travelled to Portugal in 1971 on a Gulbenkian

Foundation grant, and for three years studied printmaking and

ceramics. Portugal's Carnation Revolution of April 1974 saw an authoritarian dictatorship giving way to democracy: one of the

factors that had weakened the old order was the armed conflict

in its African colonies. Malangatana, once again an openly

declared member of Frelimo, returned to Mozambique to witness

the coming of independence on 25 June 1975.

Two years later, fighting broke out between Renamo, the

Mozambique Resistance Movement, backed by South Africa, and Frelimo. More than a million people died, either from fighting or

from starvation; five million civilians were displaced; and many

were made amputees by landmines, a continuing problem. The

civil war ended in 1992, and the first multiparty elections were

held in 1994. Throughout this time – artistically, his blue period,

which saw a number of powerful works – Malangatana was the

artistic embodiment of the continuing struggle, and took an active

role in the Frelimo government.

From 1981, he was able to work full-time as an artist, and the

following year Augusto Cabral, director of the Natural History

Museum in Maputo, commissioned him to create a mural in its

gardens. In a celebration of the unity of humankind and the often

brutal world of nature, the work depicts wide-eyed figures in

earth-coloured pastels, with extended limbs and claw-like hands.

Cabral, an ardent supporter, had played a crucial role in

Malangatana's early life. Born in Matalana, a small village north

of Maputo, Malangatana spent his childhood at various mission

schools and herding livestock with his mother; his father was

often away, working in gold mines in South Africa. At the age of

12 he ventured into the capital, then known as Lourenço Marques, where he earned some money as a ballboy at the tennis club.

He asked Cabral, one of its members, whether he had a pair

of old sandals he could spare. The young biologist – and amateur painter – took him home. Malangatana asked to be taught

painting, and Cabral gave him equipment and the advice to paint whatever was in his head. Putting aside his teenage training as a traditional healer, Malangatana did just that, encouraged by

Cabral and the prolific Portuguese-born architect Panchos Guedes, another tennis club member.

In his later years, Malangatana secured a progressive cultural development plan within Mozambique, and in 1997 was named a Unesco artist for peace. There was a dramatic shift in his artistic

output: his palette moved into a calmer rose period. He is survived

by his wife, Sinkwenta Gelita Mhangwana, two sons and two

daughters.

Duncan Campbell writes: While on an assignment for the Guardian

in Mozambique in 2005, I was fortunate enough to be introduced to Malangatana, who was then living in a large house near the airport which was part gallery and part archive. I had already been shown

some of his work, which was not only in public galleries in Maputo,

but also widely used for book covers and CDs. What was remarkable about him was that he brushed off questions about his own work and insisted instead on taking us on a magical conducted tour of local

artists from painter to sculptor to batik-maker. He was anxious that

they should receive publicity rather than him. For their part, they

clearly held him in high esteem. "He is my general," one of the young artists told me.

He was a generous and entertaining host, telling us with a smile that

his father had been a cook for the British in South Africa. A volume

of his paintings, entitled Cumplicidades, published in 2004 with a foreword by the Mozambican writer Mia Couto, illustrates the

impressive range of his work. I treasure my copy, which is inscribed

"for Dunken Cambell from my heart".

• Valente Malangatana Ngwenya, artist, born 6 June 1936; died 5 January 2011